Throughout my master’s journey, my research projects have had a common theme — trust. Below is my Capstone executive summary (master’s thesis article) related to trust and distrust in the manager-subordinate relationship. For more on my trust research, please see my blog post related to the impact of trust on the performance of cross-functional teams.

Can trust and distrust co-exist? Exploring the interplay of trust and distrust in the manager-subordinate relationship

Introduction

There is an often-told story in the trust and distrust research about a farmer in a small, rural town who set up a fruit stand along the side of the road. The stand was always left unattended, but all the fruits and vegetables for sale were prominently and freely displayed on the table. A cash box sat on the table for customers to leave payment “on their honor.” Yet, he always locked and bolted the cash box to the stand (Dawes & Thaler, 1988, as quoted in Lewicki et al, 2006).

While the farmer is trusting enough to leave the stand unattended, he assumes distrust in those who might take his money. Can trust and distrust co-exist in an organizational relationship as well? Or are they opposite ends of a spectrum that must exist in a state of equilibrium? Contemporary academics have debated whether trust and distrust are uni-dimensional, or polar opposites, or multi-dimensional, existing simultaneously. The interplay of organizational trust and distrust can be complex and nuanced, existing at the organizational level, the managerial level or the individual level. As one of the closest working relationships in an organizational setting, trust and distrust are critical dimensions in the relationship between a manager and a subordinate and can have a direct impact on outcomes like loyalty, job satisfaction, performance and organizational citizenship behaviors. Due to its importance in organizations, this research study strives to probe the research question: how do trust and distrust exist simultaneously in a subordinate’s relationship with their manager?

State of the Literature

In the academic literature, there are two distinct points of view around the interplay of trust and distrust. The first is that trust and distrust are uni-dimensional, or polar opposites, and are more of an “all of nothing” proposition that must exist in equilibrium (Luhmann, 1979; Deutsch, 1958; Barber, 1983; Rotter, 1967). Said differently, you either trust someone completely or you distrust them completely. The second point of view is that trust and distrust may exist simultaneously in multi-faceted relationships (Kang and Park, 2017; Lewicki et al, 1998; Schoorman et al, 2007).

There has been a prevalence of trust research in the last 40 years, while the study of distrust is more newly emerging. In 1958, Morton Deutsch opened the door for trust research in an organizational setting with his seminal work, Trust and Suspicion (Deutsch, 1958). In 1985, Lewis and Weigert picked up on the work done by earlier researchers like Luhmann, Deutsch and Barber to study trust’s social impact (Lewis & Weigert, 1985). In the mid-90’s, there was a proliferation of trust research published (Hosmer, 1995; Mayer et al, 1995; McAllister, 1995; Lewicki et al, 1998), all striving to put a finer point on the definition of trust. In fact, in 1998, a volume of the Academy of Management Review (vol. 23, 1998) was dedicated entirely to trust. In the introduction to this volume, Rousseau et al discuss the importance of such comprehensive trust work, stating that “efforts to date have focused more on charting the territory than probing its depths” (Rousseau et al, 1998). Trust has suffered a “definitional paradox,” (Kang and Park, 2017) and only recently have scholars adopted a generally accepted definition of trust. For the purposes of this study, the researcher used Mayer et al’s definition of trust, “the willingness of a party to be vulnerable to the actions of another party based on the expectation that the other will perform a particular action important to the trustor, irrespective of the ability to monitor or control that other party” (Mayer et al, 1995). In the example above, the farmer displays trust by being vulnerable enough to leave the fruit unattended, expecting that buyers will leave money.

While the literature on trust is extensive, much less exists related to distrust. This is due, in part, to the debate among scholars as to whether distrust is indeed a separate field of study (Kang & Park, 2017). As such, distrust has been a limited area of focus, and presents a great deal of opportunity for future research. When Deutsch published his work on trust in 1958, he did not specifically discuss distrust, but rather focused on and defined “suspicion.” Deutsch defined suspicion as the preference for disconfirmation of an event’s occurrence to the confirmation of it (Deutsch, 1958). In subsequent literature on trust and distrust, this definition is often cited as an equivalent definition for distrust. In more contemporary literature, however, distrust has been defined as the trustor’s expectation that a trustee will “approach all situations in an unacceptable manner” (Sitkin & Roth, 1993) and “confident negative expectations regarding another’s conduct” (Lewicki et al, 1998). Distrust may also be defined as a trustor’s general concern that the trustee will cause harm (Govier, 1994, as quoted in Lewicki et al, 2006). For the purposes of this study, the researcher used Lewicki et al’s definition of distrust since it is more suited to the organizational context. In the fruit stand example, the farmer is confident that the box of money will be stolen if it is not locked and bolted to the stand.

In more recent academic literature, including Costa et al’s very recent piece published in 2018, it is apparent that there is still a great deal of opportunity to understand how trust and distrust exist in different contexts within an organization, including differences between interpersonal and team trust. In fact, the authors specifically call out exploration of the “similarities and differences between low trust and distrust” as an area of future research (Costa et al, 2018).

Organizational Significance and Research Methodology

In an organizational setting, the relationship between the manager and the subordinate is critical. Trust in a leader is an input to psychological safety, which contributes to increased learning behavior, efficacy and performance (Edmondson, 1999). Leader and manager trust are also direct inputs to organizational trust (LeGood & Sacrament, 2016), which has been found to be linked to job satisfaction and increased organizational citizenship behavior (Fulmer & Gelfand, 2012). Distrust can be related to turnover, low team effectiveness and low organizational commitment (Dirks & Ferrin, 2001). The challenge for managers is that trust and distrust are hard to see, and it takes time not only to build relationships, but to truly understand the nature of them.

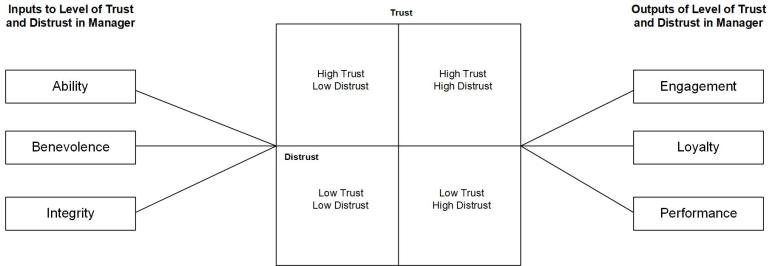

In this research study, the researcher took a qualitative approach, speaking to subordinates to understand the inputs related to levels of trust and distrust in their current manager. Then, in an effort to further the research in this space, the researcher explored the impact of these levels of trust and distrust on a subordinate’s overall relationship with their organization. The research framework is depicted in Figure 1, which defines the inputs and outputs to be studied, as well as the multi-faceted relationship between trust and distrust based on Lewicki et al’s, “Integrating Trust and Distrust: Alternative Social Realities” (Lewicki et al, 2006).

Figure 1: Research Framework

The researcher took a qualitative approach in order to discover themes or nuances that may be related to trust and distrust. A data collection instrument was developed based on the research framework, using input from prior research studies to inform question design (Adams el al, 2010; Grunig & Huang, 2000; Lewicki et al, 2006). The instrument used a series of open-ended questions as well as thirteen Likert scored questions. These thirteen Likert questions were designed to assess a research participant’s general level of trust and distrust in the manager in order to plot their levels of trust and distrust on the 2×2 matrix depicted in the research framework. The full data collection instrument may be found in Appendix 1.

Research study participants were invited by leveraging the researcher’s extended professional networks, using the following inclusion criteria:

- Employed full-time with a direct reporting relationship into a manager

- Has reported directly to that manager for at least one year

- Fifteen or more years of work experience in a professional setting

Experienced professionals (fifteen or more years’ experience) were chosen for their ability to compare current experience to past experiences. All research participants interviewed had worked with multiple managers and had varied reporting relationships over the course of their career. Eleven participants were interviewed between August and September 2018. One participant has a dual-reporting relationship to two managers so was interviewed twice to understand the relationship with each manager. All interviews were conducted over the phone and lasted between forty-five and sixty minutes. The nature of a phone interview was chosen so that research participants could participate in conversations from a location of their choosing during work hours, given the sensitive information being discussed about their manager. This approach also allowed the researcher the ability to speak with participants from a variety of geographies within the United States.

Analysis & Results

In interpreting the results, the researcher first focused on understanding the general level of trust and distrust in the manager for each research participant. Using the questions in item six of the data collection instrument (Appendix 1) and using the Likert scale responses, the researcher was able to gauge the general level of trust and distrust. Figure 2 shows a visual depiction of the level of trust and distrust that each research participant has in his/her current manager. By first assessing the general level of trust and distrust, the researcher was able to listen carefully for nuances related to the nature of the relationship. As depicted in Figure 2, seven of the twelve research participants landed in the “high trust/low distrust” quadrant. Three of the twelve research participants landed in the low trust/high distrust quadrant and two of the twelve research participants landed in the “high trust/high distrust” quadrant. None of the research participants interviewed landed in the “low trust/low distrust” quadrant. As noted above, research participant five has a dual-reporting relationship to two managers so was interviewed twice to understand the relationship with each manager.

Figure 2: Distribution of Subordinate Trust and Distrust Among Research Participants

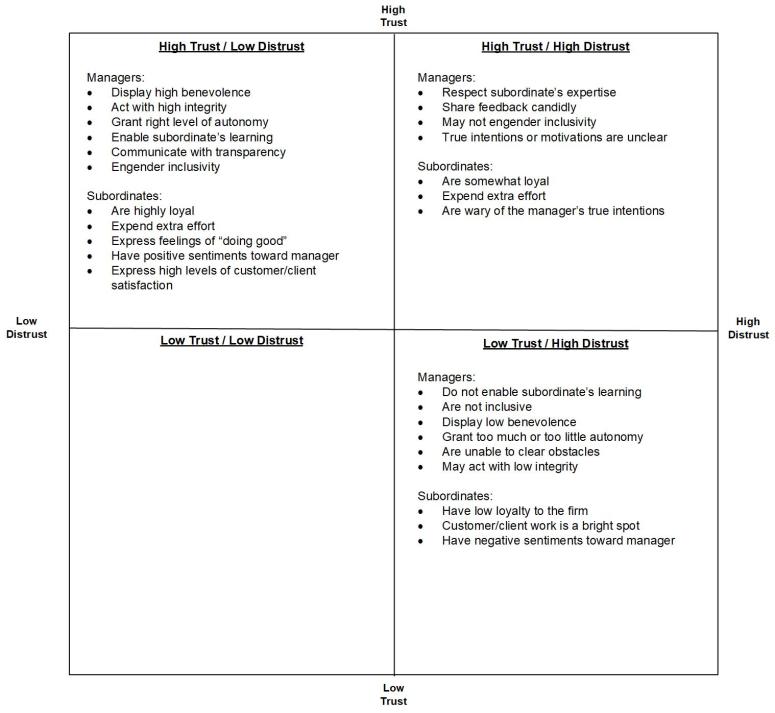

Interview transcriptions were coded based on the inputs and outputs. As nuances and themes were discovered, they were labeled for further analysis. Themes were then explored by each quadrant of the 2×2 matrix in Figure 2, with the exception of the “low trust/low distrust” quadrant, where no data points existed. In addition, some themes emerged that were not exclusive to the quadrant, but that evidence shows have an impact on the overall level of trust and distrust a subordinate has in a manager. These findings will be discussed below and are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Summary of Findings

High Trust / Low Distrust

In the high trust and low distrust quadrant, where seven out of twelve research participants generally fell, six themes emerged. Those themes are related to (1) high levels of benevolence, (2) high levels of integrity, (3) the right level of autonomy, (4) managers who enable learning opportunities, (5) managers who communicate transparently, and; (6) managers who engender inclusivity. Two of the six themes, benevolence and integrity, aligned to the inputs from the research framework shown in Figure 1.

Benevolence, or having another’s best interests at heart, was the theme that emerged most strongly from subordinates who reside in this quadrant of the matrix. In these relationships, subordinates felt that their manager “had their back.” They cited feelings of protection through statements like, “My boss will stand up and take the bullets for us no matter what.” Others highlighted the importance of benevolence for career advancement purposes, such as, “Your manager looking out for you is what’s most correlated to promotion at my organization.”

Managers in this quadrant are also regarded for their high levels of integrity as perceived by their subordinates, making statements such as “she’s guided by good moral principles,” and “I respect how she operates.” Those who did not “inherit” their manager, but rather went through a dual-selection recruitment process, cited making the fundamental decision during the interview process that “this was a good person and that our values are aligned.”

Another strong theme that emerged in the high trust / low distrust quadrant is relationships with the right level of autonomy. Sub-themes related to autonomy emerged around respect for one’s expertise, a hands-off approach and flexibility. Due to the experience level of the research participants, most of them have high levels of subject matter expertise. Managers of subordinates in this quadrant show respect for their subordinate’s expertise and their capability, especially if they have different areas of functional domain expertise. One research participant stated, “He knows that [my area of expertise] is not his world and he needed to bring in someone he had confidence in.” When this confidence is highly visible to the subordinate, it appears to foster a high degree of trust and respect for the manager. Related to this respect is a manager’s “hands-off” approach. Almost all research participants in this quadrant spoke of a manager who is “not a micro-manager,” who “engages when he needs to,” or “just wants to know about the high-level stuff.” This “hands-off” approach fosters a great deal of freedom for the subordinate in the relationship and often is accompanied by a great deal of flexibility. All research participants were also clear that this autonomy is “earned” and that they understand the trust is reciprocal that they’ll meet their performance expectations.

Managers in this quadrant also enable learning opportunities for the subordinates, however, those may not always come through learning from the manager directly. Interestingly, a theme that emerged as an input to distrust that will be discussed in greater detail below was an inability to learn from the manager. The converse does not appear to be directly correlated to low distrust, but rather a manager who enables their subordinates to learn through stretch work assignments, additional project work or professional development activity. One research participant stated, “he allows me to incorporate other things into my job that energize me.” These managers also promote transparency and engender feelings of inclusion with their subordinates, creating a psychologically safe space for reciprocal transparency, often by sharing personal information or trusting the subordinate with a confidential matter.

As a result, subordinates who have high trust and low distrust in their manager are less apt to look for opportunities outside of the organization, recognizing that they have a “good thing.” Most stated not even considering leaving for a similar opportunity and some stated that they’d follow their manager to a new organization. These subordinates are also willing to expend extra effort in exchange for the flexibility and autonomy granted by their manager, stating “He makes me more motivated to put in extra hours because I want to keep the flexibility and autonomy, it’s a perk.” They also have a general sense of “doing good,” through pride in the work they do, a sense of achievement for business or performance results, and appreciation for “an exceptional team,” as well as greater expressions of client and customer satisfaction. Lastly, all research participants expressed genuine positive sentiment toward their manager through statements such as “I have a deep amount of respect for him,” and “he’s awesome.”

Low Trust / High Distrust

In the low trust / high distrust quadrant, where three out of twelve research participants generally fell, six themes emerged. Not all sentiments expressed by these participants were polar opposites of those expressed in the high trust / low distrust quadrant. The emerging themes in this quadrant include (1) a low ability to learn from the manager, (2) a feeling of not being included, (3) low benevolence, (4) too much or too little autonomy, (5) a manager’s inability to clear obstacles, and; (6) low integrity.

When it comes to learning, one research participant stated that, “I can’t learn from him … it’s torture,” indicating that if the manager did not have anything to offer the subordinate from a developmental standpoint, it fostered distrust. This also tends to emerge when there are no check-ins or conversations to discuss professional growth. Research participants also reported feelings of not being included or being left out of critical projects or conversations, by not having a “seat at the table” or stating that “it’s a one-way relationship.”

Again, benevolence emerges as a strong theme in this quadrant, but as an input to distrust when a manager displays behavior that does not indicate that he/she has the subordinate’s best interests at heart. This often comes in the form of the perception that the manager is concerned primarily about his/her own best interests, rather than a subordinate’s or that of the team as a whole. This can also surface as visible infighting among the manager’s peer group or executive team. Autonomy also emerges as a theme in this quadrant, but it seems to be an input to distrust when it shows up in the extreme form of micro-management or a manager so hands-off that it appears he/she does not care about the subordinate or the work they do.

Participants in this quadrant also discussed, albeit not extensively, a manager’s ability to clear obstacles. This theme will be discussed in greater detail below as an indicator of “budding distrust” in a manager. Lastly, in this quadrant, participants cited numerous examples of behaviors or perceptions that suggest low integrity or unethical behavior, often showing up as divisive leadership practices, such as pitting people against each other or reporting false business results.

As a result of these inputs, participants in this quadrant generally express negative sentiment toward the organization and the manager. They show low loyalty to the firm and “would jump for the right opportunity.” However, client and customer satisfaction are still important and meetings with customers are often the bright spots in their work.

High Trust / High Distrust

Participants with high trust and high distrust (two of twelve) cited many of the same inputs to their high trust as those in the high trust and low distrust quadrant. Specifically, participants in both quadrants discussed having the right levels of autonomy and managers who encourage learning. The research participants in this quadrant are experts reporting in to C-level executives, so their autonomy is related to their high levels of responsibility and a manager who “wants results, and doesn’t want to know as much about how, but what.” They also discuss that the manager has respect for their expertise and they appreciate the acknowledgement of their knowledge in the functional domain. These managers also employ “teachable moments,” with a high degree of candid conversation about strengths and weaknesses with the subordinate.

When it comes to high distrust, in these instances, it is almost exclusively related to inclusivity, not feeling like their manager is collaborative or that they are not part of the “inner circle.” However, those who have high trust and high distrust tend to be unsure or “still assessing” their manager’s level of integrity and benevolence, even after several years. They still express uncertainty about meeting business goals and whether they’ll truly be supported in their efforts, marked by statements like “I don’t know if I have his 100% support,” and “I’m not sure she’d have my back.” Several statements related to conjecture about the manager’s level of participating in their career development or long-term opportunity suggest that they confidently don’t know their manager’s true intent.

Nonetheless, loyalty remains high in this quadrant. Research participants talked about their manager making an investment in them or taking a risk in them and wanting to see “how this plays out.” They expressed genuine appreciation for the opportunities given to them by their manager but are unsure about the future.

“Budding Distrust”

Above, the general themes related to each quadrant were discussed. However, the researcher also noticed that even those who had general levels of high trust and low distrust might show a small degree of distrust. Two themes in particular emerged relating to “budding distrust:” (1) inclusivity, and; (2) clearing obstacles. Those who had high trust but had a higher level of distrust within the high trust/low distrust quadrant stated that “sometimes things are held back.” While there was general acknowledgement that confidentiality prohibits full disclosure in many instances, there was a general desire that they wished their manager felt they could share more. In addition, a manager’s inability to clear obstacles appeared to be a spark to distrust. Whether it was a lack of power, authority or strength to push back, these were causes for distrust to be higher within the quadrant, marked by statements such as “He walked into a tough structure and doesn’t have the strength to push back enough.”

Interpretation and Recommendations

Using the research framework described in Figure 1, the researcher set out to understand if trust and distrust can exist simultaneously in a subordinate’s relationship with the manager. A qualitative approach was taken to explore the circumstances related to inputs to trust and distrust, as well as outputs, or consequences, of the level of trust and distrust a subordinate has in a manager. The conclusion of the researcher is that the interplay of trust and distrust in the manager-subordinate relationship is extremely nuanced and that it is not static. Rather, it’s a fluid dynamic that can shift among several continuums. It is not as simple as having holistic “trust” and “distrust.” Rather, there are layered elements that make up distinct inputs to trust and distrust that, on their own, do appear to exist in equilibrium. The research findings support that those elements are (in no particular order):

- Manager enables learning for the subordinate

- Manager’s ability to clear obstacles

- Manager has subordinate’s best interests at heart

- Manager communicates transparently with subordinate

- Manager is inclusive of subordinate

- Manager grants autonomy to subordinate

- Manager acts with integrity

These inputs contribute directly to outcomes related to employee loyalty and retention. In addition, when trust in a manager is high and distrust is low, employees expend extra effort which may result in higher performance and higher customer satisfaction. When distrust is high and trust is low, employees are more apt to leave the organization.

A proposed assessment for measuring inputs to the level of trust and distrust in a manager is included in Appendix 2. The researcher proposes that these items be further tested, as a means of measuring the amount of trust a subordinate (or group of subordinates) has/have in the manager through a survey or Social Network Analysis (SNA) tool. Using these items as part of a SNA will allow organizations to understand the dynamics of many relationships between subordinates and managers in a visible way, visually depicting both trust and distrust between people.

Measuring the level of trust and distrust in a manager through a SNA could be of organizational interest for several reasons. First, it may be used as a tool for determining manager effectiveness. When used in conjunction with other measurement tools such as engagement surveys, performance data and 360 reviews, it could help provide a comprehensive assessment of a manager’s overall effectiveness. A set of proposed recommendations for managers to build trust and reduce distrust based on the assessment results is included in Appendix 3.

Next, using a tool of this nature could be especially helpful for organizations going through business transformations, like a merger or acquisition, where time is of the essence. Since trust and distrust are hard to see and take time to understand, a SNA measuring trust and distrust could make invisible dynamics more visible in an accelerated way.

Lastly, when used as a self-assessment, the tool may also be useful for subordinates to better understand their relationship with the manager. A tool of this nature may assist subordinates in their reflection of their current work environments. If an individual was considering leaving the organization, this data may be part of that considerations set.

Limitations of the Study and Future Research Opportunities

This study was limited by the interview time constraints. While a significant amount of time was focused on inputs during interviews, not as much as dedicated to the outputs, or consequences, of varying levels of trust and distrust. More exploration of the impact on subordinates’ behavior as a result of their trust and distrust in the manager would be helpful to advance the research. In addition, there were no participants that landed in the low trust/low distrust quadrant. More research with more participants would have provided more data, especially in the quadrants related to high trust/high distrust and low trust/low distrust. While all research participants had fifteen or more years of experience, some had higher levels of responsibility, reporting into C-level managers. As such, perspectives may be different among those with varying job scope. This research study was conducted with experienced professionals. Further research should also be done to understand if these input elements are the same for employees at more junior career levels. Lastly, more research could be conducted to understand if these same elements could be used to measure the level of trust and distrust in other organizational relationships, such as co-workers, peers, subordinates, more senior leadership and/or non-traditional management situations.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this research showed that while the interplay of trust and distrust in the manager-subordinate relationship is multi-faceted, nuanced elements on their own do appear to exist in equilibrium. However, when taken into consideration holistically, trust and distrust may co-exist in the manager-subordinate relationship and have an impact on the individuals’ performance and overall satisfaction. When trust is high and distrust is low, employees perform better, expend extra effort, are more loyal and report better customer satisfaction. Understanding the levels of trust and distrust in the manager can help an organization to design the right interventions to build trust and decrease distrust at the individual level.

References

- Adams, J. E., Highhouse, S., & Zickar, M. J. (2010). Understanding General Distrust of Corporations. Corporate Reputation Review, 13(1), 38–51.

- Barber, B. (1983). The Logic and Limits of Trust. Rutgers University Press.

- Cialdini, R. B. 1996. Influence: Science and practice (4th ed.). New York: HarperCollins.

- Costa, A. C., Fulmer, C. A., & Anderson, N. R. (2018). Trust in Work Teams: An Integrative Review, Multilevel Model, and Future Directions. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(2), 169–184.

- Deutsch, M. (1958). Trust and Suspicion. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 2(4), 265–279.

- Dirks, K. T., & Ferrin, D. L. (2001). The role of trust in organizational settings. Organization Science, 12(4), 450–467.

- Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams. Administrative Science Quarterly,44(2), 350-383.

- Fulmer, C. A., & Gelfand, M. J. (2012). At What Level (and in Whom) We Trust: Trust Across Multiple Organizational Levels. Journal of Management, 38(4), 1167–1230.

- Grunig, J. R., & Huang, Y. H. (2000). From organizational effectiveness to relationship indicators: Antecedents of relationships, public relations strategies, and relationship outcomes. In Public relations as relationship management: A relational approach to the study and practice of public relations (pp. 23–53). Mahway, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Hosmer, L. (1995). Trust: The Connecting Link Between Organizational Theory and Philosophical Ethics. Academy of Management Review, 20(2), 379–403.

- Kang, M., & Park, Y. E. (2017). Exploring Trust and Distrust as Conceptually and Empirically Distinct Constructs: Association with Symmetrical Communication and Public Engagement Across Four Pairings of Trust and Distrust. Journal of Public Relations Research, 29(2/3), 114–135.

- Legood, A., Thomas, G., & Sacramento, C. (2016). Leader trustworthy behavior and organizational trust: the role of the immediate manager for cultivating trust. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 46(12), 673–686.

- Lewicki, R. J., McAllister, D. J., & Bies, R. J. (1998). Trust and Distrust: New Relationships and Realities. Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 438–458.

- Lewicki, R. J., Tomlinson, E. C., & Gillespie, N. (2006). Models of Interpersonal Trust Development: Theoretical Approaches, Empirical Evidence, and Future Directions. Journal of Management, 32(6), 991–1022

- Lewis, J., & Weigert, A. (1985). Trust as a Social-Reality. Social Forces, 63(4), 967–985.

- Luhmann, N. (1979). Trust and Power: Two Works. Chichester; New York: Wiley.

- Mayer, R., Davis, J., & Schoorman, F. (1995). An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709–734.

- McAllister, D. (1995). Affect-Based and Cognition-Based Trust as Foundations for Interpersonal Cooperation in Organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 38(1), 24–59.

- Rotter, J. B. (1967). A new scale for the measurement of interpersonal trust. Journal of Personality, 35(4), 651–665.

- Rousseau, D. M., Sitkin, S. B., Burt, R. S., & Camerer, C. (1998). Not So Different After All: A Cross-discipline View of Trust. Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 393–404.

- Schaufeli, W.B. (2014). What is Engagement? in Truss, C., Alfes, K., Delbridge, R., Shantz, A. & Soane, E. (Eds.), Employee engagement in theory and practice (pp. 15-35). New York: Routledge

- Schoorman, F. D., Mayer, R. C., & Davis, J. H. (2007). An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust: Past, Present, and Future. Academy of Management Review, 32(2), 344–354.

- Sitkin, S. B. & Stickel, D. (1996) The Road to Hell: The Dynamics of Distrust in an Era of Quality. In R.M. Kramer & T.R. Tyler (Eds.), Trust in Organizations: 196 – 215. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Strickland, L. H. 1958. Surveillance and Trust. Journal of Personality, 24: 200–215.

Appendix 1: Data Collection Instrument

- Tell me about your role and what you do as a <title>.

- How did you get into this type of work?

- How many years of professional experience do you have?

- What’s the most meaningful part of your job?

- What is most inspirational to you?

- What energizes you most and least about your job?

- What is the most challenging part of your job?

- Describe your relationship with your manager.

- I have a few questions related to your level of trust and distrust in your manager. You can answer each of these on a 1-5 scale, with 5 being “strongly agree” and 1 being “strongly disagree.”

- Do you believe that sound principles guide your manager’s behavior?

- Does your manager accept accountability for his/her actions?

- Does your manager have the ability to accomplish what s/he says s/he will do?

- Does your manager take more than s/he gives?

- When your manager makes an important decision, do you know that s/he will consider the decision’s impact on those who report to him/her

- Does your manager intentionally deceive you?

- Does your manager treat you fairly?

- Would your manager lie if doing so would increase profits?

- Does your manager keep his/her promises to her?

- Does your manager want power at any cost?

- Does your manager put his/her own interests above your interests?

- Does your manager care about acting ethically?

- Do you feel positive about the direction your department and/or organization is going under his/her management?

- How does your relationship with your manager affect the way you feel about your job?

- How does your relationship with your manager compare to experiences you’ve had with past managers?

- How would have answered the 1-5 questions differently based on your experience with past managers?

- How did those relationships impact your relationship with the overall organization?

- How do you tend to handle things at work when they don’t go well?

- Can you give me an example of a time when you and your manager had to work through a difficult situation?

- How difficult is it for you to detach from your job at the end of the day?

- If a new job opportunity presented itself tomorrow, how likely would you be to pursue it?

- When are you happiest at work?

- Is there anything that I should have asked but didn’t?

Appendix 2: Proposed Assessment for Measuring a Subordinate’s Level of Trust and Distrust in a Manager